No, this isn’t a post that has anything to do with Mediterranean cuisine. Gyro Night refers to an Orcadian folk observance in the Orkney archipelago (part of Scotland today), which seems to be part of the Wild Hunt tradition (and with it connections to the reward/punishment traditions found in the Santa Claus mythos) marking the end of winter and the transition into the preparations for spring in connection to a troll-woman. The folkloric tradition is recorded late, and yet I suspect it’s much older and part of heathen pre-Christian traditions. Traditionally it would have been held at a timing that should somewhat correlate to observances at Imbolc, or Candlemas (and thus in the heathen diaspora timing-wise somewhat analogous to Charming of the Plough/Disting).

The Orkneys were home to both Celtic peoples as well as later settlers from the Norse. So there was some level of syncretization. The oldest permanent settlement in the isles is at the Neolithic Era, Knap of Howar (dated to 3500 BCE) on Papa Westray island. Although there are items found in the archaeological record that date back much, much older. Many modern Orcadians have been found to genetically descend from the Norse who settled the islands in the 8th Century.

Category: The Holy Tides

Sunwait 2023 Begins

Happy Sunwait to those celebrating it!

This modern celebration that began in Sweden counts down towards the Winter Solstice and the Yuletide season. You can learn more here:

Lussi’s Night

Tonight is Lussi’s Night. In honor of the forthcoming lussevaka, the night long vigil, I decided to update my old blog entry on the Goddess. There’s so much more than what is mentioned in the graphic below (which is more fully explored, with far more information in the older blog post).

Glad Lussinatt

Sunwait – A Countdown to Yule

Yule is one of our most sacred times of the year. Not only do we have the twelve days of Yule usually bookended by Mother’s Night and Twelfth Night in our observances, we also have other celebrations like Krampusnacht (and with it the rebranding of Saint Nicholas’ Day as Oski’s Day), Lussinatt, and more throughout December and through the wassailing season, which concludes by early January. So many folk customs have persisted from what were once surely pre-Christian practices, that we get excited to have so much we can sink into as we celebrate the holy tide. We also are opportunistic, seeing traditions from mainstream religious observances around us and deciding to do our own thing that speaks to our own religious pathways.

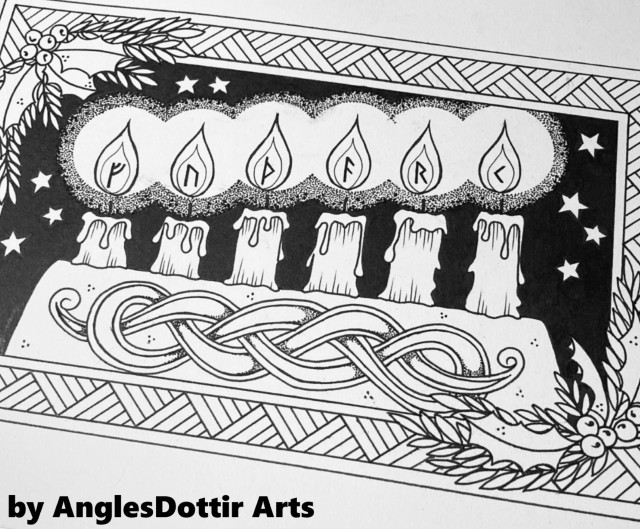

In modern times, heathens have created a new tradition in the 21st Century known as Väntljusstaken (literally, candles we light to wait) or Sunwait. Sunwait began specifically in Sweden, and it quite intentionally was started to echo Christian advent style countdowns towards Christmas. Sunwait starts six weeks before the winter solstice, and is an anticipatory lead-in towards Yule. One candle is lit per week leading up to Yule. Each candle is also symbolically tied to the first few elder runic letters: ᚠ – Fehu, ᚢ – Uruz, ᚦ – Thurisaz, ᚨ – Ansuz, ᚱ – Raido, ᚲ – Kenaz. Traditionally Thursday evening’s at sunset is when each candle would be lit, but others have created timings that work for them instead. Some decide to have it coincide with Friday’s because of work schedules, or choose instead to have each week fall on the same weekday as the winter solstice does in that given year. Still others opt to observe it on Sunday, since that day of the week is named for the solar goddess Sunna. A few people observe it as the 6 days (instead of 6 weeks) leading up to the winter solstice.

The Holy Tides – Hlæfmæsse and Freyfaxi

When it comes to religious, pagan celebrations most people are familiar with the eight holy days or sabbats that comprise the Wheel of the Year, such as Lugnasadh. In the Northern Tradition, we do not call these celebrations sabbats. Instead, based on words (like the Old Norse hátíðir) used to describe the most holy of these celebrations (like Yule) as high tides, we tend to call the various religious celebrations we recognize today as holy tides (since not all of the holy tides are considered high tides).

Since we practitioners of the Northern Tradition are dealing with a general umbrella culture that existed in vast plurality we look to ancient Germanic, Scandinavian (Norse, Icelandic, Swedish, Danish, etc.) and Anglo-Saxon sources. It is important to understand that these ancient cultures reckoned time in different ways in comparison to one another or to the modern world. They existed in different latitudes, lived amongst different types of geography with unique climate conditions that affected the local agricultural cycle. This means that sometimes the timing between when one group would celebrate and another would celebrate a similar type of holy tide could be several weeks apart.

Sometimes we can see an obvious and clear link between these cousin cultures to a specific holy tide like Yule, in other cases things are a bit less clear, or the celebrations of the different groups can sometimes seem vastly different even when they have a similar root, or some celebrations may be unique and not echoed in extant sources elsewhere.

Hlæfmæsse translates in our modern English tongue to Loaf-Mass, and is sometimes also called Lammas, we have numerous instances in Anglo-Saxon literature that talk about this particular Christianized celebration and some of the traditions attached to it. Since mass denotes a Christian ritual, some have theorized that the pre-Christian name for this holy tide may have been Hlæfmæst (feast of loaves), and for this reason some Heathens will use this name instead. That theory may not be far off reality. The ninth century text, Old English Martyrology, refers to August 1st as the day of hlæfsenunga, which translates to ‘blessing of bread’.

Holy Tides of the Northern Tradition – Charming of the Plough

For many pagans, this is the time of year where they honor and celebrate Imbolc one of the eight sabbats that comprise the Wheel of the Year. For those of us in the Northern Tradition however, we have our only celebrations known as holy tides (from the Old Norse hátíðir) that we may currently be celebrating instead: Charming of the Plough or Disting.

Since Northern Tradition religious practices can vary because some groups and individuals opt to recreate the celebrations of geo-specific historic cultures, others look at the vast umbrella that we see amongst the Æsic-worshipping peoples as they appear throughout ancient Germania, into Scandinavian countries (like Sweden, Norway, Iceland, etc.), and into Anglo-Saxon England.

The timing of these holy tides varies based on regional differences in the seasonal transition of climate, as well as in the different time-keeping and calendar methods that were employed by the different cultures when compared to the modern-day calendar used today. Some timing may have also shifted as pagan observances were shifted and syncretized in an intentional joining by early church leaders in post conversion Europe. As a result, while some Heathens opt to sync the timing up with the quarter-day of Imbolc so that their holy tide celebration occurs at the same time as their pagan cousins, others have already celebrated, and yet others more may not be celebrating for a few weeks yet.

Still, in my experience, most Heathens sync up their observance with the astronomical midpoint between the winter solstice and the spring equinox in a more generalized Charming of the Plough observance. This also coincides approximately with the modern Groundhog Day. For those unfamiliar with the custom of Groundhog Day (and I’m not referring to the movie), the folk tradition comes from the Pennsylvania Dutch. Despite the name being ‘Dutch” these weren’t settlers from the Netherlands, but rather they were Deutsch, or German. Specifically speaking their own dialect called Deitsch with language ties to West Central Germany. English speaking Americans misheard this and thought it was ‘Dutch’ and the name stuck. There’s a lot of interesting folk traditions from these European settlers, and if you look among those Pennsylvania Dutch traditions you’d find an array of folk traditions including hex signs, runes, and folk stories about gods–like Wudan (Odin), Dunner (Thor), Holle (Frau Holle or Holda) etc. This presence of folk tradition has given us another branch (albeit it far less known) within the Northern Tradition umbrella: Urglaawe. The settlers we call the Pennsylvania Dutch have a tradition of using a groundhog as a weather predictor for when spring would arrive. The custom back in Europe where these settlers originated seemed to have used the badger instead. Knowing when spring might arrive would be a very important indicator for people to know when to make ready the fields and more importantly plant the crops for the year ahead. Too early, and you’d lose the crop to winter’s frosty bite. So this folk tradition operated as a nature based omen as a sort of farmer’s almanac. While there is no scientific evidence that this custom has any true accuracy, I think the key takeaway here is the timing of early February and the fact this custom ties to the importance of agricultural timing while balancing the change of the seasons to make ready for the year ahead.

According to Bede’s De temporum ratione, the Anglo-Saxon month of February was known as Solmonad, and meant month of mud. Most likely mud month refers to the act of ploughing the fields. According to Bede, this was a time celebrated by people offering cakes to their Gods. The only other time we see offerings of cakes ever mentioned as occurring is with the celebration of Hlæfmæsse (loaf mass), which occurs at the opposite time of year at the time of the harvest. So here we have a mirrored tradition of offerings of cakes or loaves given to the land as a bookmark to the growing season (planting to harvesting).

In England, there is a folk tradition known as Plough Monday (which was the first Monday after the Christian celebration of the Epiphany or Three Kings Day which marked the end of the Christmas/Yuletide). Today that means Plough Monday is celebrated the first Monday that falls after January 6, and features the ceremonial act of ploughing the first furrows in the fields. While the earliest written depictions of this tradition come from post conversion (1400s CE), it is in all likelihood a surviving remnant of the pagan past. Plough Monday is celebrated today in many communities across the United Kingdom (Yorkshire, Cambridgeshire, etc.), while some local traditions vary, typically a village plough was blessed, decorated, and a ceremonial ploughing around the village was carried out. This tradition mirrors what we see in the Anglo-Saxon land ritual the Æcerbot (or Field Remedy).

As an aside, I find it striking that we see this timing of just after January 6th echoed for another major rite among heathen lands, save this time in what we associate with Lejre in Denmark (the probable real world setting for the mythic tale of Beowulf). In chapter 17 of The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg, it states “Because I have heard strange stories about their ancient sacrifices, I will not allow the practice to go unmentioned. In those parts the center of the kingdom is called Lederun (Lejre), in the region of Selon (Sjælland), all the people gathered every nine years in January, that is after we have celebrated the birth of the Lord [Jan 6th], and there they offered to the gods ninety-nine men and just as many horses, along with dogs and cocks— the later being used in place of hawks.” We see similar types of sacrificial offerings mentioned by Adam of Bremen in chapter 27 of History of the Archbishops of Hamburg in regards to the rites at Uppsala in Sweden (though the specific timing is not mentioned in the source). But we know from Ólafs saga helga that the sacrifices at Uppsala did coincide with Disting (which usually took place typically in February (but it did vary base on the lunar cycle). [More on Disting further below.]

Among the traditions of Plough Monday there is also a tradition of going around trying to earn everything from drink to money, which to me is reminiscent of other caroling and wassailing traditions. Additionally there’s also dancers, and a straw bear (man in straw outfit) which to me evokes other traditions like the Perchten and Krampus processionals. January seems awfully early for some of us to think about readying the ground for new plantings. England while it exists at a more northern latitude that typically would mean much colder winters (see how much colder it is in parts of Canada at the same latitude), the land benefits from its proximity to the Atlantic oceanic currents, or Gulf Stream, which keeps England much warmer than it would be otherwise. So this is but one example of why some Heathens choose to observe this holy tide when it makes sense to do so in their own local climate.

Plough Monday may be an English tradition, but so too is the Anglo-Saxon Æcerbot. While the earliest known recording of this tradition references Christian belief, many believers and scholars believe it was adapted from pre-Christian practices. The daylong ritual was intended to act as a means to restore fertility to land that may not be yielding properly, or was potentially suffering from some sort of blight or infestation. In the ritual described the land is symbolically anointed and blessed before being plowed, we see that the plough is hallowed and even anointed with soap and herbs too, and the personified (and no doubt deified) earth is invoked and entreated for her blessings.

The ritual may have lasted a day, but in most likelihood it would take even longer to prepare. It required taking four sods of earth from each of the corners of your land. The earthen sods would be anointed with a mixture combining oil, honey, yeast, milk (from each cow on the land, and possibly any milking animal like goats too), bits of each tree growing on the land (except hornbeam which is a type of tree in the birch family, this caveat is suggested to refer to all trees not harvested for food), bits of each named herb growing on the land (except glappan, we’re not sure what that herb was referring to in England some have tried to liken it to buck bean used for a plant native to the Americas known for being both bitter and growing in marshy areas so it most likely referred to some sort of unwanted weed), combine with water. The mixture (probably combined into a paste like what we see in the Anglo-Saxon Nine Herbs Charm) is then dripped 3 times on the bottom (soil side) of each of those pieces of earthen sod. All this while essentially praying over it to grow, and multiply in bounty followed by an invocation (of the saints in the remnant we have that was recorded).

Not done yet, the rite then has the farmer/landowner taking those sods of anointed earth into town to the church where a priest would bless it (singing four masses over it). There was a ritual structure in turning the earth while this occurred so the green and growing side faced towards the altar. Then the farmer had to hurry home before sunset to put the anointed and now blessed earthen sod back from whence it came. Praying over it again. Marking it with symbols (the cross) made from mountain ash (possibly rowan) and ground meal in those corners. Each corner invoked the name of a saint (and pre-Christianity probably invoked various deities). The earth is then re-interred from whence it came, one corner of earthen sod at a time. Each time the farmer prays over it, tuning the earthen sod eastward, after which the farmer would bow nine times praying (possibly originally to the Goddess Sol as her brightening days would be key to agricultural cycles and growing). The farmer with arms outstretched was to turn 3 times sunwise while reciting even more prayers. (As an aside this Anglo-Saxon source isn’t the only time we see bowing to the east, in the Icelandic Landnámabok it mentions bowing to the east to hail the rising sun. So this teases to a cultic habit that may have existed across the Germanic tribes.)

Now that the earthen sod that has been cut from the land, anointed, blessed, re-interred and prayed over we proceed to the next step: ploughing of the fields and sowing of the seeds. The farmers/landowner is handed seed by his men (presumably those in service to him, or other members of the household). This would make sense to divide some of the labor, as the farmer/landowner has bee very busy up to now with the ritual requirements of the earthen sod. So his people bring out the plough and related gear, they are the ones to anoint you, the ones to hand the farmer his seed. The plough is described as being anointed with soap, salt, frankincense and fennel–obviously this has been influenced by Christianity which we can tell by the inclusion of frankincense, and salt makes it a market of Medieval Europe too. Some in the Northern Tradition umbrella look to another Anglo-Saxon reference, that of the Nine Herbs Charm and use that mixture–consisting of the nine herbs Mucgwyrt Mugwort, Wegbrade Plantain, Stune Lamb’s cress, Stiðe Nettle, Attorlaðe (theorized to be either cockspur grass or betony), Mægðe Mayweed, Wergulu Crab-apple, Fille (theorized as either thyme or chervil), and Finule Fennel–combined into a paste with old soap and apple residue.

The farmer begins to plow, and to pray to the personified earth. In Tacitus’ Germania we see a mention to the Germanic tribe of the Angli (eventually after migration they would settle into a land that would become named for them: Angle-Land or England) “were goddess-worshippers; they looked on the earth as their mother.” Scholar Kathleen Herbert argues that the Æcerbot comes from the Angli’s religious traditions.

Whole may you be [Be well] earth, mother of men!

– Æcerbot

May you be growing in God’s embrace,

with food filled for the needs of men.

Afterwards, special offerings of cakes or baked loaves (made from whatever was the farmer’s grain crop) were placed into the first furrows that had been ploughed. Really consider the level of detail and preparation needed for a ritual like this. This was a MAJOR undertaking, and as such makes it clear this was a major celebration of great import. I think sometimes when so many of us don’t work the land directly, and rely on grocery stores and uber for our food we can forget the amount of time, the vulnerability that can come with being the sole provider of your own food. Farming was very much a matter of life and death.

Aspects of the ritual structure in Æcerbot, are reminiscent of hallowing land or even land-taking rituals that we see in a variety of other sources. These land-taking customs can be seen in the Icelandic Landnamabok, where men might walk around their property with fire, or women who were claiming land could only claim what they could plough in a day from sunrise to sunset. There are folk-traditions in areas of Russia (so named for the Viking Tribe known as the Rus) that describe women ploughing around their communities as a charm against disease outbreaks, so like the Æcerbot which is to make well the land again, we see another tie between plowing and health in this folk tradition.

The ploughing story and land-taking we see most famously with the Danes, when the Goddess Gefjon is seen ploughing the fields with her Jotun (giant) sons in the form of great oxen. The ploughing of this Swedish soil was so deep that the land was uprooted, leaving a lake behind, the uprooted land was named Zealand, and is the most agriculturally ripe part of the Danish countryside today. For this reason, those Heathens who celebrate the Charming of the Plough may honor Her in their celebrations, though others may opt to honor instead the other Goddesses found in our tradition of the Earth, such as the Germanic goddess Nerthus.

There are several scholars (as well as Heathens today) who see a link between Nerthus and Gefjon. In Tacitus’ Germania, he writes of Nerthus:

“There is a sacred grove on an island in the Ocean, in which there is a consecrated chariot, draped with cloth, where the priest alone may touch. He perceives the presence of the goddess in the innermost shrine and with great reverence escorts her in her chariot, which is drawn by female cattle. There are days of rejoicing then and the countryside celebrates the festival, wherever she designs to visit and to accept hospitality. No one goes to war, no one takes up arms, all objects of iron are locked away, then and only then do they experience peace and quiet, only then do they prize them, until the goddess has had her fill of human society and the priest brings her back to her temple.”

Here are two Goddesses, both associated with cattle and the earth, and both who dwell on islands. But more than just this similar motif, scholars see that the medieval place name for the modern-day city of Naerum in Denmark was Niartharum, which etymologically may connect to Nerthus’ name.

In addition to Charming of the Plough, we also have the Swedish known holy tide of Disting as observed in Uppsala. Disting was partly comprised of the Disablot (a special communal ritual to the Disir) as well as a regular Thing gathering. Rituals to the Disir exist at several different times in sources, some we see at the Winternights celebration, another at Yule’s Mother’s Night, and another in the aforementioned Disting, which suggests that observance of the Disablot varied. While the worship of the disir existed throughout the Northern Tradition umbrella, the timing of ritual observances varied by unique geo-specific cultures and their own traditions. The Disir embody the protective female spirits that look after individuals, their families, and the tribe or community. As such Goddesses and female ancestors comprise the Disir, but also most likely the spirit loci as well.

Things, as seen throughout the ancient world, were gatherings of people with appointed representatives where legal matters were discussed, people came together in the spirit of trade, marriages might be sought, and typically were also marked by religious rituals. In pre-Christian times the Swedish Thing at Uppsala happened several times a year at this location, but after the conversion to Christianity only one Thingtide was still observed, the one that fell at this time of year, specifically at Candlemas (a Christian feast day celebrating the presentation of the child Jesus to the Temple observed on February 2nd). While this Thingtide kept its original timing, (no doubt from syncretization of old traditions with the newer Christian religion) the religious aspects of the gathering were removed post conversion.

In Heimskringla’s Ólafs saga helga, we have a description of the rites at Svithjod (The Thing of All Swedes, of which Disting/Disablot was a component): “In Svithjod it was the old custom, as long as heathenism prevailed, that the chief sacrifice took place in the month Gói (sometime around Feburary 15th until March 15th) at Upsala. Then sacrifice was offered for peace, and victory to the king; and thither came people from all parts of Svithjod. All the Things of the Swedes, also, were held there, and markets, and meetings for buying, which continued for a week: and after Christianity was introduced into Svithjod, the Things and fairs were held there as before. After Christianity had taken root in Svithjod, and the kings would no longer dwell in Upsala, the market-time was moved to Candlemas, and it has since continued so, and it lasts only three days. There is then the Swedish Thing also, and people from all quarters come there.”

In another section of that text, we have a description of a Disablot, which suggests that the King in Sweden oversaw the ritual in his role as High Priest while ritually riding around the sacred hall. Just as we have aspects of land-taking in stories of Gefjon, or as exhibited in the Æcerbot or Plough Monday traditions, we can understand that it is likely that the King’s riding on his horse probably ritually connected to some aspect of land-taking or boundary making as well.

Land-taking isn’t just for the past either. If you look at the way the “Freedom to Roam” laws operate, as seen throughout Europe (including Norway, Sweden, England, Scotland, Wales, etc.), this ancient concept is still in a sense being used. In the case of the Freedom to Roam, it grants rights to citizens who responsibly and without harm to the property, traverse it so they can have access for the purposes of exercise and recreation to these undeveloped parcels of land, or lands specifically set aside for community use like common land and village greens. In other areas, these rights of access to the common land are only upheld so long as at least once in a stipulated period of time it has been used. In some areas there are community-wide traditions where all the able-bodied people will go on a walk to make sure they keep these areas ‘claimed’ as common land. For this reason, some of the more hardy Heathens may opt for a camping trip at this time of year.

There is an 8th century text, indiculus superstitionum et paganiarum, that mentions that in the month of February there was a celebration still on-going in Germany called Spurcalia. Spurcalia is a Latin name used to describe the celebration, and it is believed that it roots to the German word Sporkel, which meant piglet. In fact in parts of Germany the month of February was actually called piglet-month, or Sporkelmonat, and the Dutch name of the month is the very similar Sprokkelmaand. The assumption is made that with the first livestock births of the year occurring, that pigs were most likely sacrificed at around this time. While this is an obscure reference even to most Heathens, there are a handful who use Spurcalia as their inspiration for making sure there’s some pork on the altar given in offering to the Gods and Goddesses.

So how can we celebrate this today?

While most of us when we consider agricultural celebrations we think of deities of the earth and the associated fertility Gods and Goddesses, such as Freyr, Freyja, Gerda, Gefjon, Nerthus, etc. Aurboda is the mother of Gerda and mother-in-law to Freyr. While little is known of her she is a deity of healing and one presumably with a tie to the earth as well. I suspect her skill probably comes with the knowledge and application of herbs: how to find and grow them, how to reap them, how to store and prepare them, and how to use them. For this reason I will also make sure she is honored at this time. In Gylfaginning, Freyr is said to rule over “rain and sunshine and thus over the produce of the earth; it is good to call upon him for good harvests and for peace; he watches over prosperity of mankind.” Thor also has connections with this time, not just as a god of storms and rain but with healing too. We have one reference to him as being a protector for the health of a community. In the Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum, Adam of Bremen records that at the Temple of Uppsala, “if plague and famine threaten, a libation is poured to the idol Thor.” So we see him tied specifically to famine, which of course would come about by impacts to the crop by weather. With his wife the Goddess Sif being a deity of grain crops it might make sense to honor her as well. Sunna makes sense as well since it is by her light that plants grow.

I also like to incorporate into the festivities Wayland (or Volund), who was a blacksmith. After all, blacksmiths represented the luck of a community. They helped to craft the tools used in the agricultural process: ploughs, hoes, shovels, pick axes, shoes for the livestock, etc. By connection we can also think of this as a time of the dwarves (many who we see are tied with the blacksmithing creation of certain tools for the Gods), for where does the metal come from that a blacksmith uses, if not from us mining the earth?

While most of us today don’t make our livelihoods directly from the land, we can still understand this time of year as the time meant to prepare ourselves for the workload ahead, which is why many Heathens who celebrate the Charming of the Plough may ask for blessings regarding career prospects, job offers and other related elements for the coming year. Some groups may have rituals where people and the ‘tools’ of their trade are blessed. A tailor might bring their scissors to be blessed, a writer might bring a pen, people may bring their security badges for places they work, or anything else that seems appropriate.

If you’re a farmer you may want to create a modified version of the Æcerbot for your own practices. On a smaller scale whether you are a homeowner, or merely live in a place without access to your own land you can plant your own edible plants and do a mini version of the rite, even if it’s just a potted plant of kitchen herbs, or perhaps a gardening plot to grow some of your own fruits and vegetables for the year. The baking of loaves and the offering thereof is still incredibly relevant, and probably the most common element of this holy tide among modern practitioners today.

When talking about the ritual structure of the Aecerbot, I mentioned the nine herbs charm and how it was create as a mixture with soap, apple residue and the noted nine herbs. If we look to the Northern Tradition we see that Idunna the goddess with the golden apples that gives vitality to the gods, has Bragi the god of music as her husband. We know in some areas around the end of the Yuletide the apple orchards were sung to as part of wassailing traditions, in order for them to bear fruit in the coming year. So when I see similar wassailing folk traditions with Plough Monday, I see a continuation and a thought of the need to sing to the land. To invoke the deities of the land. The reference to apple residue being used in the Nine Herbs Charm, depicts to me a connection with the concept of vitality in our tradition because the apple is the fruit and source of vitality: vitality of life, and vitality of the land. You won’t have fresh apples anymore, but even in their residue and seeds there is power. So, while Idunna tends to be more regularly invoked from fall through the end of Yule, there may be something poignantly appropriate about adding something related to apples to your offerings. Not fresh apples as that’s not seasonal, but the sort of products that can be made and stored from apples picked in the fall. Maybe some apple butter to go with your offering of loaves. This can be part of other seasonally appropriate herbs, flowers, and produce for your offerings too.

A Mother’s Night Prayer

Tonight as the sun sets begins the Yuletide for me with Mother’s Night.

To friends near and far, may you have a joyous Yuletide blessed with the laughter or friends and family (even if socially distanced). May the Gods and our ancestors continue to bestow their blessings upon us, and strengthen our luck for the days that lie ahead.

For those with difficulty reading the graphic…

Let us honor our Mothers, who through joy and suffering endured so that their children, and their children’s children might not just survive but thrive.

I call to our mothers, the light and the life bringers who have guided us from darkness onto the paths our ancestors have traveled, and now the paths we walk down.

All-mother Frigga I hail thee, and I thank thee. For the immeasurable blessings, your guidance and your wisdom. You see all things, even if I may not know them. May your counsel follow me into the year ahead and be the compass from which I navigate.

May the blessings of the Disir be upon you all.

Wyrd Dottir, Mother’s Night Prayer

Glad Lussinatt

Yule is a magical time of year, and when we look to the various holiday traditions from Krampus and Saint Nicholas, to the celebration of Saint Lucia Night, we see the pre-Christian customs as remnants scattered across all of December. But I wanted to acknowledge Lussi (also known as Lusse, Lucy), as her feast day approaches. Unfortunately most information about her doesn’t appear in English, but primarily in folk traditions and their accounts from Norway and Sweden (and therefore, in those languages). Usually what we find in English relates more to the Christianized syncretization, and the church’s “Saint Lucia” story.

Some scholars have posited that the Christianized Saint Lucia and the customs tied to her celebration in modern times is most likely a syncretization of pre-Christian customs of Lussi (from areas of Norway and Sweden, and possibly other areas of influence from the Germanic tribes) with the Italian Christian martyr Saint Lucia. Folk traditions describe Lussi having a Wild-Hunt (oskorei) like horde called the Lussiferda.

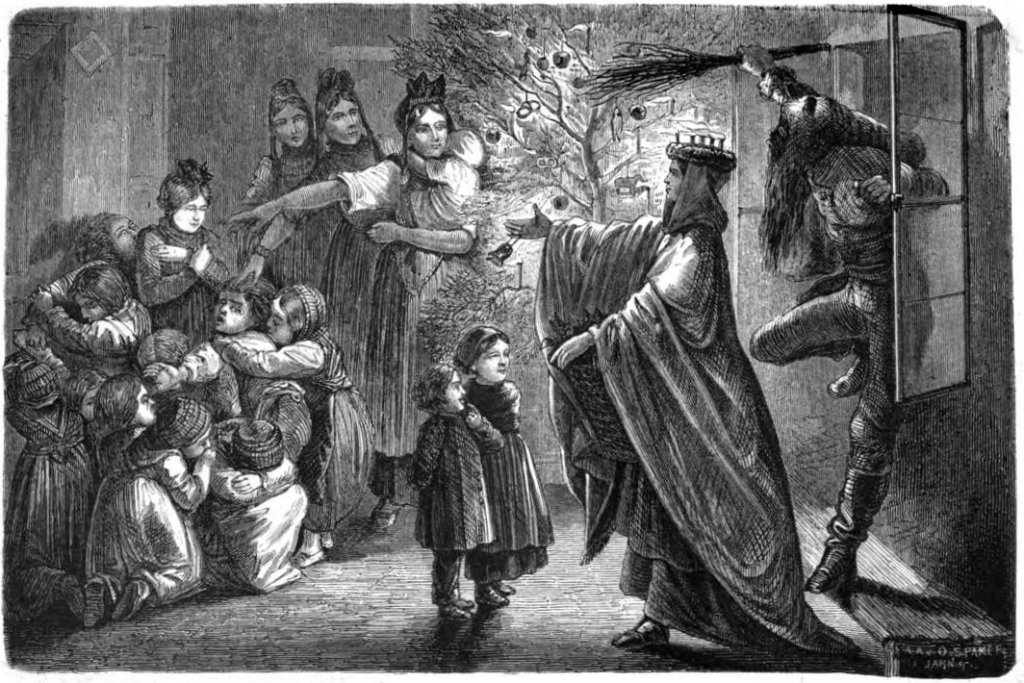

The figure is about 150 cm high (4.9 feet) and was used before 1930. The Nordic Museum.

In some regions of Sweden there would be the lussebrud (the Light Bride). Sometimes the lussebrud was merely a female dressed for the occasion, but sometimes this may be a male or female dressed up in straw as a bride, or the lussebrud may be a straw doll. The lussebrud may also be accompanied by the lussebock (Light buck). This is similar to other Wild Hunt figures in the Northern Tradition: Perchta & the Perchten, Saint Nicholas (possibly influenced from Odinic origins) and the Krampus. Like other Wild Hunt figures, she has ties to the reward/punishment folk traditions. Lussi or her horde would come down chimneys and steal misbehaving children. Lussi might destroy chimneys if certain tasks weren’t done before her night: spinning of thread or yarn was to be finished, cleaning finished, slaughtering for the year to get through the winter, and other such tasks. Symbolically, these were all tasks you’d need to help you survive a winter. If people hadn’t finished all their work, they feared Lussi would smash their chimneys.

The celebration of Lussi’s Night was meant to be culturally connected with the winter solstice, and that is what we see with the older Julian calendar. We can tell this from the clue we have of the celebration’s name from parts of Norway, where it was called ‘Lussia Langnatte’ (or Lussi’s Long Night). In Sweden it’s usually referred more simply as Lussinatta (Lussi’s Night). When a new calendar methodology was adopted, the Gregorian Calendar, we ended up with her celebration on December 13, and the astronomical solstice falling about a week later.

Today in Sweden, Lussinatt falls on the evening of December 12. There exists a multiplicity of folk traditions that can mark the celebrations. Some are secular, some are tied to the church. Previously as we near the modern era, you would have lussegubbar, or youth dressed up like Lussi and go carousing door to door in the countryside singing, in a tradition that seems reminiscent of caroling and wassailing traditions we see elsewhere. Today the songs are still sung especially the Sankta Lucia (which is believed to originate from an Italian folk song, rebranded with Swedish lyrics), but the processions are a bit less wild as they tend to wind their way through town from schools and churches, to nursing homes and hospitals. Today many towns will have an elected (or chosen by random lottery) Lucia who leads the procession (Luciatåg) wearing a candled wreath (known as a luciakrona, which was traditionally worn as a crown decorated with evergreen lingonberry branches), accompanied most usually by young girls as her handmaidens (tärnor) in evergreen wreath crowns and more recently young boys as star boys (stjärngossar) in pointed white hats holding gold stars. Everyone is all dressed in white holding candles. Sometimes they are also accompanied by gingerbread men (pepparkaksgubbar), or in some places they might dress as the local elves.

Traditionally the crowns were adorned with real candles and open flames. But in a move towards safety most places have shifted to using electric lighted versions of the candled wreath instead. In addition to the crowns there are also more candle-ladened items associated with the observance called Ljuskrona (ceiling mounted chandelier) or Ljustaken (table-top candelabara) usually, though some other names include: julstaken, julkrona, or jul tradet. Sometimes they were adorned with handcut and fringed paper decorations, different patterns were known to be prevalent in specific communities in Sweden. These Ljustaken are usually hidden until December 13, then brought out and decorated. It’s quite common for this to be a family activity. They would be part of the decorations in the home throughout the entirety of the yuletide until January 13, when they are put away again until next December.

The practice of Lussevaka – to stay awake through Lussinatt (the evening of December 12) to guard oneself and the household against evil, not only fits symbolically well with a solstice celebration of longest night, but also brings to mind the description from Bede that Mother’s Night was observed for the entire night as well. Today, it’s not uncommon for there to be parties as part of the lussevaka observance, sometimes with people actually cooking and making the lussekatter rolls they’d eat in the morning. People may use the time to work on handcrafted projects. Some will drink and be merry with their peers. There are old references to folk traditions of writing Lussi’s name on doors and fences or in other areas of having weapons at hand (or hanging them up) while you observed the vigil. In some areas, you were meant to feast to keep you strong through the terrors of the night. It was a night where animals were said in some areas to be able to speak, telling Lussi what evil they may have witnessed. Livestock in some areas were given a treat of extra food, or a lussebit, meant to help them survive the evil that may lurk during the long night. There’s some folk customs that include women invoking Lussi for oracles on their future husbands.

“In Denmark, too, St. Lucia’s Eve is a time for seeing the future. Here is a prayer of Danish maids: “Sweet St. Lucy let me know: whose cloth I shall lay, whose bed I shall make, whose child I shall bear, whose darling I shall be, whose arms I shall sleep in.”

-Clement Miles (referencing Jacob Grimm)

This parallels somewhat to traditions we see in Lower Austria.

St. Lucia’s Eve is a time when special dbu from witchcraft is feared and must be averted by prayer amid incense. A procession is made through each house to cense every room. On this evening, too, girls are afraid to spin lest in the morning they should find their distaffs twisted, the threads broken, and the yarn in confusion. (We shall meet with like superstitions during the Twelve Nights.) At midnight the girls practise a strange ceremony: they go to a willow-bordered brook, cut the bark of a tree partly away, without detaching it, make with a knife a cross on the inner side of the cut bark, moisten it with water, and carefully close up the opening. On New Year’s Day the cutting is opened, and the future is augured from the marking found. The lads, on the other hand, look out at midnight for a mysterious light, the Luzieschein, the forms of which indicate coming events.

Clement Miles

The mention of cuts on the tree bark harkens to other customs across the Northern Tradition umbrella, including folktales of Woodwives, Moss People, the Buschgroßmuttter, even some other wild hunt Goddess figures (Walpurga, Berchta, Frau Holle) and trees explored in the folktale collections of Rochholz’s Drei Gaugöttinen: Walburg, Verena und Gertrud, and Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology. Winifred Hodge once theorized that the cross shape may have possibly been a nauthiz rune (ᚾ) in heathen antiquity.

Lower Austrian customs speak of a procession through the house. In other areas of Europe the eldest daughter in her role as light bringer might walk the property with her candle from house, through barn and stable, and around the boundaries of the farmstead to ward it from evil. One imagines in pre-Christian times this was probably accompanied by prayers of invocations to the Holy Powers for protection, the prayers and incense mentioned in the lower Austrian customs.

In Northern Europe, especially some of the most extreme latitudes, there can be very, very little daylight indeed. Northern most areas of Sweden have around 2 hours of sunlight on the winter solstice. We know that lack of sun can be a lack of both mental well-being, but physical well-being as well causing vitamin D deficiencies. The celebration marks the start of the holiday season. On the morning of December 13, households will designate a member of the household (usually the eldest daughter) to serve drinks and baked treats including pepparkakor (ginger snap cookies), mulled wine (glögg), coffee as well as saffron baked goods like cookies or the more iconic treat lussekatter in honor of Lucy’s Day.

Saffron featured prominently in Gotland, Sweden by the 1300s, lending itself to inclusion in the iconic Gotland Pancake (saffranspannkaka) that was a treat of the yule season. It may have made it to Sweden much earlier, albeit in limited distribution, because the Vikings had extensive trade routes. We do know that the Romans used to cultivate saffron in southern Gaul, and we have evidence of old Roman recipes using the ingredient such as jussele, mentioned in Galfridus (Anglicus)’ Promptorium parvulorum sive clericorum. Gaul was an area populated with Celtic tribes that we know Germanic tribes had interactions with (plus, they had interactions with the Romans, too). So it’s possible the spice was known to the Germanic peoples (at least some of the elite) long before booming in popularity in the Middle Ages.

Saffron then, as well as today is one of the most expensive spices in the world. Saffron only blooms once per year for two weeks. Each bloom has 3 pistils that must be harvested by hand just after sunrise for full flavor efficacy once the bloom opens for the day. Over 150,000 flowers have to be harvested this way to net just 1 kilogram, or 2.2 pounds of spice. So any food made with saffron already denotes it as a special dish reserved for important celebrations, but the harvesting for this foodway preserves sacred connection to the sun. The yellow color used in those saffron spiced treats are a nod to Lussi’s connections as a light bringer. One presumes the eating of these treats in the morning once the sun has pierced the darkness once again could be the conclusion in some areas to the warding of the property from the night before, and the corresponding nightlong vigil.

While there’s a few different Christian origin stories for Saint Lucia (or Lucy), one of them has her bringing light to persecuted Christians hiding in the catacombs surrounded by the dead with nothing but a lit wreath to guide her. Symbolically, traversing the dark and realm of the dead with light, seems to fit with pre-Christian symbolism. There is another story of how a woman with golden radiance appeared in a boat with food during a time of great hunger as well, who disappeared once the food was delivered. Another comes from what seems to be an attempt by the Church to demonize her, saying she was another wife of the Biblical Adam that consorted with Lucifer, and the unholy product of their union would be the demons or lussiferda.

The traditional depiction of Saint Lucia is of a woman clad in white. We know this is sacred iconography that is referenced time and again in Northern Tradition areas. We see this mentioned in Tacitus’ Germania that priest or priestesses wore white, we also see in the folk traditions mentioned by Grimm that women clad in white appeared at dawn for Ostara/Eostre.

Lussesang – A Song for Lussi

While I don’t agree with the song’s description saying this is for Freya (and thus assuming that Lussi is an aspect of Freya), the lyrics only mention Lussi and Alfrodul (an attested name for Sunna) and the lyrics are perfect for Lussinatt. If you visit this song on youtube, you can find the lyrics in Swedish and English if you expand the description.

Hail to you Lussa holy among the holy, the bright dis of Yule. Drive with your light from the valleys of the Earth the darkness of midwinter.

(Excerpted English translated Lyrics from Lussesang)

At its heart this is a festival of lights in the darkness where observed in Europe, including Sweden, Norway, Finland, as well as parts of Estonia, Croatia, and Italy. Denmark began observing it in 1944 when Franz Wend imported it from Sweden as a cultural counter protest to Nazi Germany and their occupation of Denmark. Plus across the diaspora of communities created through Swedish immigration elsewhere. The Nordic Museum has a small gallery of photos of Lussinacht celebrations from the first half of the 20th Century.

I will leave you with this striking, cinematographic observance of Lussi’s Night “Light in the Darkness” by Jonna Jinton, an artist, musician and filmmaker living in the northern woodlands of Sweden.

*Updates:December 2, 2021 with Swedish terminology.December 10, 2022 with information about saffron rarity, harvesting, and references.

I made use of The Nordiscka Museet’s website, they had an amazing bibliography, referenced below in addition to some other sources as well.

References

- Alver, Brynjulf. 1976. Lussi, Tomas og Tollak: tre kalendariske julefigurar. I Fataburen : Nordiska museet och Skansens årsbok 1976. Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Arill, David (red.). 1923. Västsvensk forntro och folksed. Göteborg.

- Andersson, Ingvar m.fl. (red.). 1956-1978. Kulturhistoriskt lexikon för nordisk medeltid från vikingatid till reformationstid. Malmö: Allhem.

- Bergstrand, C. M. 1925. Lucia i Västergötland. I Folkminnen och folktankar, Bd 12. Göteborg: Västsvenska folkminnesföreningen.

- Bringeus, Nils-Arvid. 1998. Lucia, Medieval Saint’s Day – Modern Festival of Light. I Arv: Nordic Yearbook of Folklore, Vol. 54. Lund: Btj.

- Bringeus, Nils-Arvid. 1981. Årets festseder. Stockholm: LT i samarbete med Inst. för folklivsforskning.

- Campbell, Åke och Nyman, Åsa (red.). 1976. Traditioner knutna till Lucia-dagen, 13 december. I Atlas över svensk folkkultur. 2, [Kommentar], Sägen, tro och högtidssed. Uppsala: Lundequistska bokh.

- Celander, Hilding. 1936. Lucia och Lussebrud i Värmland och angränsande landskap. I Sigurd Erixon och Sigurd Wallin (red.). Svenska kulturbilder, Bd 3, Ny följd, D. 5-6. Stockholm: Skoglund.

- Celander, Hilding. 1928. Nordisk jul. Stockholm.

- Celander, Hilding. 1950. Stjärngossarna: deras visor och julspel. Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Dys, Johan. 2004. Källmaterialet och gestaltningen – en studie kring Luciafirande i Malungsdräkt utifrån historiska källor och nutida kulturarvskontext. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet, Etnologiska institutionen.

- Ehrensvärd, Ulla. 1979. Den svenska tomten. Stockholm: Sv. turistfören.

- Ernvik, Arvid. 1977. Erik Fernows Beskrivning över Värmland, ny utg. Karlstad: NWT.

- Eskeröd, Albert. 1973. Årets fester. Stockholm: LT.

- Falke, Ursula. 1982. Saffransfläta duger att äta: en studie av saffransbrödets förankring i Sverige. Lund: Lunds universitet: Etnologiska institutionen med Folklivsarkivet.

- Forbes, Bruce David. 2007. Christmas: a candid history. Berkeley, Calif ; London : University of California Press.

- Grimm, Jacob. Deutsche Mythologie. 1880. [translated as Teutonic Mythology by James Steven Stallybrass across four volumes from 1880-1888]

- Hammarstedt, Edvard. 1898. Lussi. I Meddelanden från Nordiska museet. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Hedin, Nathan. 1931. Från Lussemorgon till Knutkväll. I Karlstads stifts julbok. Karlstad: Karlstads stiftsråd.

- Hellström, Hans. 2012. Sankta Lucia. Stockholm: Katolsk bokhandel : Veritas.

- Jobs Arnberg, Anna-Karin. Giftas på låtsas. I Dan Waldetoft (red.). Lekar och spel : Fataburen : Nordiska museets och Skansens årsbok 2014. Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Johansson, Levi. 1906. Lucia och de underjordiske i norrländsk folksägen. I Fataburen : kulturhistorisk tidskrift. Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Knuts, Eva. 2007. Mockbrides, Hen Parties and Weddings, Changes in Time and Space. I Terry Gunnell (red.). Masks and mumming in the Nordic area. Uppsala: Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien för svensk folkkultur.

- Kujala, Anja. 1996. Luciafester bland svensk-amerikaner i New York, så som de framställs i tidningen Nordstjernan på 1920-, 1950- och 1980-talen.Stockholm: Stockholms universitet, Institutet för folklivsforskning.

- Kättström Höök, Lena. 1995. God jul!: från midvinterblot till Kalle Anka. Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Kättström Höök, Lena. 1999. Seder vid frieri och bröllop. I Täpp John-Erik Pettersson och Ove Karlsson. Mora: ur Mora, Sollerö, Venjans och Våmhus socknars historia. 3. Mora: Mora kommun.

- Liungman, Waldemar. 1944. Luciafirandet och dess ursprung: något om en svensk-tysk folktro. Lund: C. Blom.

- Löfgren, Anders. 2007. Luciatraditioner av idag. I Årsbok : Garde robe 2006. Stockholm: Föreningen Garde robe.

- Löfström, Inge. 1981. Julen i tro och tradition. Älvsjö: Skeab.

- Lönnqvist, Bo. 1969. Lucia i Finland. Innovation och etnocentricitet. I Folk-liv: acta ethnologica Europaea: svensk årsbok för europeisk folklivsforskning 1969. Lund: Folk-liv.

- Magnus, Olaus. 1976. Historia om de nordiska folken. Kommentar: John Granlund. Stockholm : Gidlund i samarbete med Inst. för folklivsforskning vid Nordiska museet och Stockholms univ.

- Marin, Otto Ulrik. 1837. Ingen ting, eller om småfolkets sällskapslif i staden och på landet : en “sketch-bok” till lands. Stockholm: Hjerta.

- Marttila-Strandén, Elsa. 1981. Stjärngossesed och Lucia. Åbo: Åbo akademi.

- Miles, Clement A. 1912. Christmas in ritual and tradition, Christian and Pagan. London.

- Modéus, Martin. 2000. Tradition och liv. Stockholm: Verbum.

- Nilsson, Martin P:n. 1936. Årets folkliga fester, 2. utvidgade uppl. Stockholm: Geber.

- Piø, Iørn. 1992. Den nye jul i tekster og billeder. København: Sesam.

- Piø, Iørn. 1978. Julens hvem hvad hvor: håndbog om julens traditioner. København: cop.

- Resare, Ann. 2007. Från nattsärk till festklänning. I Årsbok : Garde robe 2006. Stockholm: Föreningen Garde robe.

- Resare, Ann. 1988. Och bruden bar … I Ingrid Bergman (red.). Kläder : Fataburen. Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Rochholz, E.L. Drei Gaugöttinen: Walburg, Verena und Gertrud, als deutsche Kirchenheilige. Sittenbilder aus germanischen Frauenleben. Verlag von Friedrich Fischer, Leipzig, 1870.

- Rudbeck, Ture Gustaf. 1864. Femtiofyra minnen från en femtiofyraårig lefnad, D. 1-2 sammanbundna. Stockholm.

- Schön, Ebbe. 1989. Folktrons år: gammalt skrock kring årsfester, märkesdagar och fruktbarhet. Stockholm: Raben & Sjögren.

- Skjelberd, Ann Helene Bolstad. “Jul i Norge”. 2014. [ISBN: 9788283050141]

- Stjernswärd, Brita. 1938. Herrgårdsliv för en mansålder sedan. I Fataburen : Nordiska museets och Skansens årsbok 1938. Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Strömberg, Lars G. 1996. Lussegubben – en djävuls historia. I Tyst, nu talar jag! : tradition, information och humanister : populärvetenskapliga föreläsningar hållna under Humanistdagarna den 12-13 oktober 1996. Göteborg: Humanistiska fakultetsnämnden, Univ.

- Swahn, Jan-Öjvind & Bergman, Anne (red.). 2000. Folk i fest – traditioner i Norden. Stockholm: Fören. Norden.

- Swahn, Jan-Öjvind. 1993. Den svenska julboken. Höganäs: Wiken.

- Tajani, Angelo. 1996. Varför firar vi Lucia? [folktron, kulten, traditionen, legenden]. Höör: 2 kronors förl.

- Tamm-Götlind, Märta. 1961. Hur firade västgötarna lucia i gammal tid?. I Falbygden: årsbok 1961. Falköping: Falbygdens hembygds- och fornminnesförening.

- Terént, Mia. 2004. Loppor och löss går igen. I Christina Westergren (red.). Fataburen : Nordiska museet och Skansens årsbok 2004. Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Wennhall, Johan. 1994. Från djäkne till swingpjatt. Om de moderna ungdomskulturernas historia. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet.

- Ödman, Pelle. 1910. Litet till. Stockholm: Hellström.

Krampusnacht and Oski’s Day

On the eve of December 5th throughout parts of Europe, Krampus makes his appearance. The strange creature sent to punish naughty children. On the morning of December 6th however, Saint Nicholas has made his appearance leaving small gifts or sweet treats for those children who were nice.

If we look to Europe we can see a connection between Wild Hunt figures and the Santa Claus mythos tied to a concept of reward and punishment. We also see that the Norse god Odin has connections to the Santa Claus mythos as well in more than one way, but especially as he has three epithets that connect to the holytide listed in the skaldic poem Óðins nöfn: Oski (God of Wishes), Jólnir (Yule Figure) and Jölfuðr (Yule Father).

There is a small movement among Northern Tradition polytheists to reclaim December 6th, and celebrate it not in honor of Saint Nicholas, but rather in honor of Odin in his guise as Oski. The purpose is not to break the bank with this, but rather to share a little yuletide cheer. Edible treats typical of the season (cookies, candy, chocolate, apples, oranges, nuts) would be appropriate, and other small trinkets. In other parts of the world, including America, we have instead the tradition of setting out stockings Christmas Eve for Santa to deliver some goodies for us. So to think of ‘stocking stuffers’ is a good rubrik in terms of what to gift, but I offer this caution: the ‘stockings’ we so commonly use in our decorations are ridiculously big. In Europe, for December 6th it is shoes that are filled, most commonly a shoe is placed outside the door, though in some households they may opt to have a designated area where the shoes are left. Some will use their actual shoes, but others will use special clogs kept just for the holiday for these purposes (which is a nicer way to avoid shoes that are stinky). So there’s not alot of real estate available to fill up with goodies. This is not where to show your gift giving American largesse.

Just as there are traditions for leaving out milk and cookies for Santa on Christmas Eve, and maybe some carrots for the reindeer, in parts of Europe they may leave some hay, carrots or other appropriate treat in the shoes for St Nicholas’ white horse. Many Northern Tradition polytheists will instead include treats for Odin’s horse, Sleipnir. This is a tradition that lends itself well to the magic of the season, and especially to those with younger children. But even as I write this I set on a small collection of wrapped goodies I’ve received from friends and kindred members, waiting to open them on December 6th, and I have a few small things that I’ve sent off to others as well with instructions they have to wait till the 6th.

You must be logged in to post a comment.