As Heathens the times we most tend to look at in the past are the historical periods where we have intersection between textual manuscripts and archaeological finds, starting from the Pre-Roman Iron Age (500-1 BCE) where Caesar writes of the battles with Germanic tribes, through the Roman Iron-Age (1-400 CE), then into the Germanic Migration Period (which peaked around 375-568 CE) culminating in the Viking Age (793–1066 CE), and sometimes even post conversion examined into the late Medieval period. But examining preceding time periods in the region can give us some insights even though culture and religious practices changed. So there can be some value in looking at the adjacent Iron Age Cultures like Jastorf Culture (6th C BCE – 1st C BCE) and La Tene Culture (450 BCE – 1 BCE), and preceding Bronze Age cultures like the Hallstatt culture (1200 – 450 BCE, which we associate more with later Proto-Celtic culture), and the Nordic Bronze Age (1750–500 BCE).

The Nordic Bronze Age (1750 BCE – 500 BCE) was characterized by a significant and highly prevalent sun cultus, many see in the Trundholm Sun Chariot archaeological find an echo to similar stories within the Indo-European umbrella, but what is more recognizable for Heathens is what appears to be an earlier iteration we later recognize as the story of Sunna and her chariot within Norse cosmological myths. So you can look even further back to try to trace certain threads of belief and praxis (such as examining the wagon processionals).

One of (if not the earliest) surviving account of Germanic tribal solar lore comes to us from first century Roman historian Tacitus’ Germania, that states “beyond the Suiones [tribe]” a sea was located where the sun maintained its brilliance from its rising to its sunset, and that “[the] popular belief” was that “the sound of its emergence was audible” and “the form of its horses visible”. Among Northern Germanic cultures we see the story reverberate.

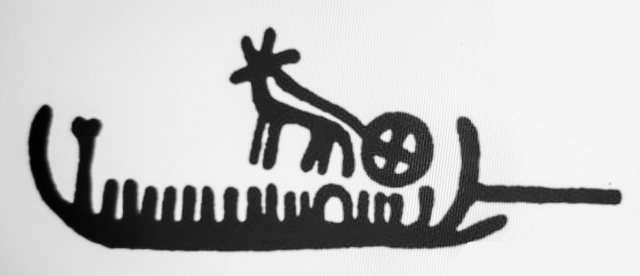

But the concept of the sun with horses dates even further back, the Nordic Bronze Age (1700–500 BCE) seems to have focused heavily around a sun cultus. We have an inscribed glyph of a horse with sun on a razor found at Neder Hvolris near Viborg, and a petroglyph at Fossum (near Tanum). There’s other figural inscriptions and glyphs too.

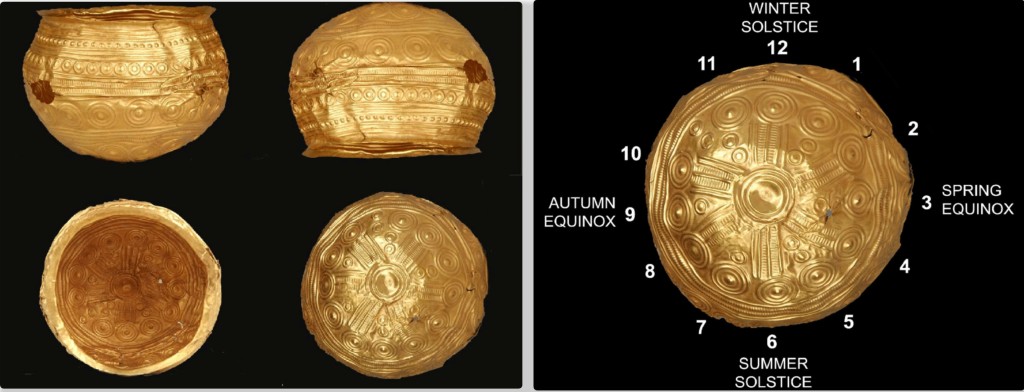

In the archaeological record we have the Nordic Bronze Age item, we’ve called the Trundholm Sun Chariot (1400 BC), which was found in Odsherred (Denmark), alongside other offerings in a bog. The chariot’s wheels are solar crosses, which we find across the archaeological record (on some of the stones on the Kivik’s King Grave, on solar crosses found near Zurich, the Balkåkra Ritual Object (and the nearly identical counterpart the Hasfalva Disc), petroglyphs from Tanum in Sweden, and so many more). The item depicts a Sun in a horse drawn chariot. One side was clearly enhanced with gold adornments and gildings, and the other side was kept intentionally dark. Both sides feature swirls as a design element. Archaeologist Klavs Randsborg presents a theory that it represents an astronomical calendar of synodic months (as published in his article “SPIRALS! Calendars in the Bronze Age in Denmark” in the Adoranten journal).

There are different theories for the dual sided nature of the sun disc from the Trundholm Sun Chariot. One theory is the dark side represents a connection to the underworld. Another is that the dark side represents night, especially considering we have lore that the moon was also pulled in a horse-drawn chariot, or perhaps the dual nature of the sun disc is a division of the year into two seasons: summer and winter. Randsborg’s theory looks at the swirls as representative of a synodic calendar splits the sun disc sides into day and night. “The reference is to the Sun-calendar on the day-side, and to the Moon-calendar on the night-side of the Sun Chariot, which seems the perfect calculation.”

We think the Trundholm Sun Chariot was made using a cire perdue casting (lost wax process), and thus there’s a chance there could have been a re-usable mold. While we have no firm evidence of this, we do have other examples of sun discs in the archaeological record, suggesting a shared cultural symbology, and thus possibility of similarly casted objects.

The burial find of the Egtved Girl, gives us a sun disc in the form of a belt along with other elements of clothing for a female. Because of the specialness of that belt, and the fact analysis of her remains tells us she traveled extensively in the last two years of her life, there is some speculation she may have been a priestess in a sun worshipping cultus. Randsborg also believes that the annulus of swirls on her famous belt represents the progress of solar time. In addition to the aforementioned Trundholm Sun Chariot, and the Egtved Girl’s belt, we also have pieces of a sun disc found at Jægersborg Hegn (Denmark), which is from another site in the Trundholm area. The National Museum of Denmark posits an intriguing question for the Jægersborg Hegn sun disc, could it have also been a part of a sun chariot?

As an aside, the Egtved Girl’s outfit, specifically her skirt, seems to connect to the skirt we see on what we think is an acrobat on one of the bronze figures uncovered in Grevensvænge (Denmark), which appears to represent ritual performers. We have numerous petroglyphs that show similar acrobatic figures on various rock carvings found at multiple sites (one example follows). Considering the clothing and the acrobatic figure, I do think it incredibly likely that the Egtved Girl was a person fulfilling a cultic role. Acrobats/dancers, musicians seem to have been a key component of processionals. Not only do we have Nordic Bronze Age era objects that depict religious processionals, but we see some similar aspects of a processional carry into later objects like the Oseburg Tapestry (Norway), and Garde Bote Stone (Sweden).

Returning to the topic of solar imagery, we have even more examples of shared sun iconography, but we begin to transition away from discs, to bowls and urns. The golden urn from Mjövik (Sweden), when you turn it upside down has spokes and swirls rendering a posited calendar, echoing variations on the solar cross in some instances.

The urn is similar to a variety of archaeological finds in the National Museum of Denmark’s collection, consisting of gold offering bowls with similar swirl design, as well as horse-necked bowls believed to also tie to the iconography of the Sun being pulled by a chariot from a variety of sites: Mariesminde (Denmark), Boeslunde (on the Borgbjerg Banke in Denmark).

In addition to some of the offering bowls found in the Boeslunde region, around 2000 gold wire spirals were also unearthed. One of the National Museum of Denmark’s curators, Flemming Kaul theorizes the spirals may have been part of cultic regalia, perhaps worn by a priest/ess.

We also have a handful of golden tall conical hats that have ben found in the archaeological record, such as the one from Avanton in France, dated to around 1400 BCE. Also the Golden Hats of Schifferstadt, Ezelsdorf-Buch, and Berlin. The later lacks the provenance of where it was discovered and is named for the location of the museum where it is housed. Like the Sun Disks, analysis of the hats seems to indicate their function in part as a lunisolar calendar (per Wilfried Menghin’s Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica).

These Nordic Bronze Age (1700–500 BCE ) objects predate the time period we typically examine as Heathens (which starts with the Iron Age of 500 BCE, especially once the Germanic tribes come into contact with the Roman Empire, through the late Iron Age period of Germanic Migration. The Iron Age ends around 800 CE with the start of the Viking Age which is where the majority of the area falls under conflict and eventual conversion to Christianity. For most, the Viking Age ends in 1066 CE with the Norman conquest of England. But others continue to look at the region’s artifacts, manuscripts and history until 1300 CE). But the Nordic Bronze Age is the directly preceding time period, the descendants of said people would have been among the Germanic tribes (and the Celtic tribes). As the symbolism of sun and horse echoes in later Norse myths, I do to my mind find it a reasonable assumption of continuous worship.

“An influential study on the narrative aspects of Late Bronze Age iconography is Flemming Kaul’s work on decorated bronze razors (Kaul 1998). By examining the motifs on the razors he was able to demonstrate that individual motifs on different razors were logically linked to each other into a larger narrative revealing the travels of the sun through the sky during the day and beneath the sea at night. At different points on its journey, the sun was helped by various agents such as a sun horse, a fish and a snake, which all held specific functions within the narrative. The designs on individual artefacts depict particular stages in that cycle, and only when several razors are put together is the whole cycle revealed. It seems as if all the drawings found on decorated metalwork illustrate sections of the same story (Kaul 2005).” Levels of Narrativity in Scandinavian Bronze Age Petroglyphs by Michael Ranta, Peter Skoglund, Anna Cabak Rédei and Tomas Persson

Academic researcher and curator at the National Museum of Denmark, Flemming Kaul notes that many of the solar boat imagery in the boats (representative of an actual boat believed to have been part of a votive offering of weapons, tools, a sacrificed horse and more found in the bog at Hjortspring Mose), shows travel to the west from left to right interpreting it as the day, in the same way as we see the sun moves from east to west on the southern sky. The opposite movement is night. We can take that further and theorize that the left to right journey represents life from birth through death.

Flemming Kaul has shown (1998; 2004) a convincing path to an evidence-based interpretation of the Bronze Age iconography of southern Scandinavia. In short, he has discovered how circle motifs on bronze razors in more than 50 instances appear in combination with ships sailing in a specific direction, towards the right, while they are never seen together with ships sailing towards the left – except in one case where both a ship sailing right and one sailing left are present (Kaul 2004, 242; Kaul 2020). Through this observation, and by including the Trundholm chariot, whose golden side is similarly visible when it is moving towards the right, he puts forward a direction-based thesis that offers to explain the Bronze Age people’s conception of the sun’s daily movement across the sky (ibid.) (fig. 2). The strength of this interpretation is that it goes beyond mental connections and gut-feelings, as the statistical testimony of the motifs on the razors, and the corresponding logic of the Trundholm chariot, serve as a foundation for Kaul’s reasoning. — Mikkel Christian Dam Hansen’s Interpreting a Bronze Age motif – Revisiting the hand signs of southern Scandinavia

The National Museum of Denmark tells us that the sun had more helpers than just the sun, we know this because we find fish, birds, serpents, horses, deer, wagons and boats among petroglyphs from the Nordic Bronze Age. We have numerous kennings in the literature connecting water and horse, to SHIPS, what follows is a small sampling:

| KENNING | TRANSLATION | SOURCE |

| hesta hafs | of the horses of the sea. SHIPS. | Ragnars saga loðbrókar |

| bráðra sóta barðs | of the swift steeds of the prow. SHIPS. | Gyðingsvísur |

| kapla brimis. | of the horses of the sea. SHIPS | Plácitusdrápa |

Sometimes we see the solar symbolism combined. We actually have a petroglyph from Bohuslän, Östergötland (Sweden) that combines solar wagon with solar ship imagery. We think the Germanic Migration Era & Viking Age tradition of boat shaped graves, and actual boat graves derives in part from Bronze Age life and death beliefs combining solar boats and solar chariots with life and death beliefs. So in the Germanic areas, water and sun has long been tied. Drunertos from the Brittonic polytheism website Albion and Beyond mentions an article on death beliefs (and boats) for Gaulish and Proto-Germanic peoples at Jonas Jacobson’s article on the afterlife that is worth a read.

In Sweden there’s a massive 67 meter long structure of stones, known as the Ales Stones. The rocks are roughly in the shape of a boat, but with an analysis via archeoastronomy, we can tell that the stones are arranged in an alignment to both the Summer, and Winter solstices. The Stenhed Stones , are another stone ship outline with celestial alignments to the solstices. We also see in the Brantevik graves alignment too.

The famous Oseburg Ship Burial tapestry has the swastika symbol on it, which is believed to be a type of solar cross symbol. The tapestry shows a religious, possibly funerary processional (which may echo some content from the Nordic Bronze Age’s Kivik’s King Grave) with wagons. But the tapestry was a grave good, found within a boat burial grave. So we have a boat grave, a tapestry with solar symbolism and the likely depiction of a funerary procession with wagons and horses traveling to the left (and potentially perceived as the west).

Not only do myths tell us that horses pulled the sun chariot, but In the Germanic tradition, and seen also among the Scandinavian sources horses were incredibly sacred. Tacitus’ Germania describes them as being milk-white–and similar to the sanctuary we see centuries later at Thrandheim–the equines were housed in sacred groves where they were never used for the purposes of riding or working the land. Horses in Germania were described as being more sacredly close to the Gods then even their priests; somehow these horses were in the Gods’ confidence. For this reason horses were used in acts of hippomancy to divine the will of the Gods. They were yoked to a special sort of chariot and their behavior observed. In the neighboring Slav culture we also see horses used in divination as well (but via a different method). We have even older evidence of an active cultic presence connected with horses in even the Bronze Age, and we see in the law codes in Europe during the period of Christian conversion that the eating of horse-flesh was forbidden because it had ties to heathen religious tradition. We see in the Historia ecclesiasstica Islandiæ that Christian priests were forbidden from attending horse-fights as well (most likely for a similar reasoning). Horses had not only a divine connection, but also have a role in the agricultural cycle as well. In Norse Myth horses also pull the chariots that draw not only the Sun, but the Moon as well through the sky.

So from a perspective of Germanic belief and the preceding Bronze Age culture(s) we see ties of horses, solar cultus with wagon, boats, water, life and death.

There are a number of named horses in the lore. The most famous of which is surely Loki’s son, the stallion Sleipnir ridden by Odin over sea and through air. Similarly, the Goddess Gna’s horse, Hófvarpnir, can move through air and over the sea, too. Plus, many others are described in both the Poetic and Prose Eddas as carrying the Gods on their journey over the bifrost to make judgments at Yggdrassil. Grani, and Freyr’s horse can tolerate fire, and most likely Skinfaxi, Alsviðr & Árvakr can tolerate fire too. There are so many more named horses in the lore.

Horses in the Lore:

- Alsviðr (Sunna)

- Árvakr (Sunna)

- Blakkr

- Blóðughófi (Freyr)

- Fakr

- Falhofnir (Æsir)

- Fölski (Sturluson’s horse)

- Freyfaxi (dedicated to Freyr)

- Garðrofa (parent of Hófvarpnir)

- Gísl (Æsir)

- Glaðr (Æsir, maybe Dagr)

- Glær/Glenr (Æsir)

- Goti (belongs to Gunther, brother of Sigurd)

- Grani (son of Sleipnir, Sigurd’s horse)

- Gullfaxi (originally owned by Hrungnir, later given by Thor to his son Magni)

- Gulltoppr (Heimdall)

- Gyllir (Æsir)

- Hamskerpir[ (parent of Hófvarpnir)

- Hófvarpnir (Gna)

- Hrafn (2 horses by this name. The first belongs to King Eadgils, the second is given to King Godgest)

- Hrímfaxi (Nótt)

- Jor

- Lettfeti (Æsir)

- Lungr

- Marr (is a harbinger of the guardian spirit fylgja)

- Morr

- Silfrtoppr (Æsir)

- Sinir (Æsir)

- Skaevadr

- Skeiðbrimir (Æsir)

- Skinfaxi (Dagr)

- Sleipnir (Son of Loki, Odin’s horse)

- Slöngvir (King Eadgils)

- Soti

- Stuffr

- Svaðilfari (Sleipnir’s Father)

- Thegn

- Tjaldari

- unnamed horses (belonging to Mani, Baldr, the valkyries)

- Valr

- Vigg

Gutorm Gjessing theorized there was probably at one point a Germanic horse god in his Hesten i forhistorisk kunst og kultus, tying it with fertility and how we eventually see those connections with the God Freyr. I am reminded of the hippophagy we find in the Völsa þáttr, where we have a mention in the lore to the cultic use of an equine phallus as a symbol of worship to a deity. Centuries earlier we see Germanic worship as encapsulated among the votive inscriptions to the Celtic Goddess Epona from Roman Imperial Europe. Epona was a rarity, a non-Roman deity that enjoyed widespread worship throughout the Roman Empire, especially among the military cavalry. We have found inscriptions to her from the Germanic tribe of the Batavii, which is mentioned in M. P. Speidel’s book Riding for Caesar: the Roman Emperors’ Horse Guards.

We have Germanic remnants of a divine duo of Gods (we see them presented we believe euherimistically in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) known as Horsa (horse) and Hengist (stallion), whose names are represented in the architectural twin horse-necked gables referred to as “Hengst und Hors” as has been found in areas of Germany such as Lower Saxony (Hanover especially) and Schleswig-Holstein. Those gables were a design motif we see in modernity inspiring the set design of Edoras in Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of the Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers based upon the fictional story by J. R. R. Tolkien. Horsa and Hengist may be analogous to the divine twins Tacitus names as the Alcis (their name etymologically believed to connect to elks) worshipped by the Germanic tribe Naharvali. In turn through interpretatio romana they were seen as similar to the Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux; aka Gemini), who were often depicted with horses and they were beloved of sailors. In fact we see them on a votive altar where we see both horses and a ship.

Lind and Mörner in their Mykenska och Feniciska spår på Österlen, and Kristiansen & Larsson’s The Rise of Bronze Age Society, explores connections between the Nordic Bronze Age and the wider Indo-European Culture, especially with Mycenaen Greece. We have strikingly similar iconography at times between the two.

This isn’t terribly surprising considering scholars have grouped Germanic languages and cultures under the greater Indo-European umbrella, along with the ancient cultures of Greece and Rome, all of which have solar deities (Helios & Apollo, Sol) driving the sun in chariots/wagons. Even in Hinduism we have the solar deity Surya with a sun chariot.

In Rock Art and Religion by Kristian Kristiansen, the scholar posits that the Nordic Bronze Age petrogylphs were based on a shared Indo-European myth of a sun Goddess and her brothers who come as horses or ships to help the sun move across the sky as most likely evidenced by the divine twins (such as: Hengist, Horsa; Castor, Pollux; the Alcis; etc.).

The Norse Goddess Sunna/Sol In the Lore

In various stories from the Poetic and Prose Eddas, we learn of Sól (Sunna), and how she is tied to the movement of the sun, especially in Vafþrúðnismál, & Gylfaginning. She appears elsewhere in the lore too from Skáldskaparmál full of kenning and other poetic names for her. The Second Merseburg Incantation (also known as the “Horse Cure Charm”), dates to around the 9th or 10th Century. The Merseburg charms are the only examples of pre-Christian Germanic belief recorded in the Old High Germanic language. The context of the story is that Baldr’s horse has been injured, and so the Gods and Goddesses present (Wodan, Frig, Fulla, Sunna & her sister Sinthgunt) render healing aid to the horse.

In the Poetic Edda, specifically within the Volupsa it states:

Sól það né vissi

hvar hún sali átti,

stjörnur það né vissu

hvar þær staði áttu,

máni það né vissi

hvað hann megins átti.The sun knew not

where she a dwelling had,

the moon knew not

what power he possessed,

the stars knew not

where they had a station.

-Poetic Edda, Völuspá, Benjamin Thorpe translation

Here we see Sol/Sunna, Mani, and the “Stars” being written about by means of seeming personification, and therefore most likely deification as well. This to me, strengthens the concept of a possible connection between Sunna and Sinthgunt, and suggests this may be a trio of siblings. Cosmologically, Sunna and Mani’s father, and in my opinion most likely Sinthgunt’s as well, is Mundilfari the time turner. His name etymologically refers to “periods of time”, and it makes sense that his children would be the references we use to count time. Today we still mark time by the progress of the sun, the moon, and the stars.

In the lore we are given insight into the importance of the sun, by being told of its different names among the different races of Norse cosmology (giants, dwarves, etc.). When Thor asks Alviss what is the name of the sun in all the worlds:

Alvíss kvað:

“Sól heitir með mönnum, en sunna með goðum,

kalla dvergar Dvalins leika, eygló jötnar,

alfar fagrahvél, alskír ása synir.”

Alviss spake:

“Men call it Sun, gods Orb of the Sun,

The Deceiver of Dvalin the dwarfs;

The giants The Ever-Bright, elves Fair Wheel,

All-Glowing the sons of the gods.”

-Poetic Edda, Alvíssmál, Bellows translation

While religious structure changed from the Nordic Bronze Age to what we see later among the Germanic tribal diaspora, while we seem to see a prominence by the Viking Age to male divinities, the female deities seem to fall in popularity. Terry Gunnell’s article “Pantheon? What Pantheon? Concepts of a Family of Gods in Pre-Christian Scandinavian Religions” (published in SCRIPTA ISLANDICA: ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK 66/2015) touches upon the theories of hierarchy, and a common pantheon to a more tribal and varied one as he summarizes the scholarship on the matter and shares his own thoughts.

I have seen through the years fellow heathens talk about how the sun wasn’t worshipped by heathen times, and yet in the Landnámabok, it mentions bowing to the east to hail the rising sun. In Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar there is a mention to the ritual of miðsumarsblót (midsummer sacrifice), so while details are lacking, we do see another suggestion of lingering importance in the Viking Age.

Across the Northern Tradition umbrella we see that they didn’t have a concept of four seasons, but only two: summer and winter. So the start of Summer is spring, and the start of Winter is fall. Failing to understand this can confuse you on the timing of certain celebrations. But to confuse matters further, unique regions would have their own timing based in part on local cues.

Also, we know the Germanic tribes viewed the day as beginning at sunset, we see this remain in the word fortnight, but also within the name of some of our holy tides: Mother’s Night, Winter Nights, etc. Roman sources relate that the Germanic tribes held special relevance to nights of the new or full moon to gather for either ritual, or business. We know they used various versions of a lunisolar calendar. This meant they first and foremost, they followed the lunar phases, but also did something to try to align the year with the solar cycle as well. Prior to the adoption of the Julian Calendar, year keeping was super complicated, with extra intercalary weeks, days and even months added (as needed). What we know comes from either Tacitus’ Germania (which looked at customs on mainland Europe) and later Bede’s De Temporum Rationae (which looked at customs in what we think of as England today). In Bede we know that we have two months back to back one called Ærra Gēola (before yule) the other Æfterra Gēola (after yule), and another dual combination of Ærra Līþa (before litha) and Æftera Līþa (after litha)–plus a sometimes third month of litha, the intercalary Þrilīþa, which was sometimes shoehorned between the two other months of midsummer when needed. Giving us a sense today as we sift through these sources, that the solstices were definitely used as key factors in the solar portion of the calendar, and most likely retained even if not specifically mentioned in extant sources cultic importance to our solar and lunar deities.

Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology (originally published in 1835) describes the traditional folk practices for Midsummer celebrations in the areas where the Norse Gods were once venerated included the use of a sunwheel (or a wagon wheel) on fire. In some cases the wheel was simply lit locally and incorporated into the Midsummer bonfire. In other cases people trekked out into the countryside, found a hill, set the sunwheel on fire, and let it roll down the hill as they chased after it, people watching and cheering as they watched it roll along it’s fiery way, as vegetation caught fire. Sometimes mini-fires were set in the fields, as a way of directly burning in offering the crops that the sun had helped to grow, or fragrant herbs were tossed into local bonfires instead.

As for me, midsummer is a holy day where I make offerings and venerate Sunna.

by Wyrd Dottir

Hail Sunna

Daughter of Mundilfari the time-turner,

Sister of light-gleaming Mani,

Wife of Glenr, and fair mother,

We hail you.

Day-Star, Light-Bringer,

Elf-Beam, Ever-glow,

All-bright, fair-wheel,

Year-counter

We greet you.

Shining grace bestow upon us,

Healing hands lay upon us,

Blessings of warmth, joy and plenty

We ask of you.

Hail to thee Sunna,

Dancing Fire of Sky and Air,

Lady of the Midnight Sun,

Golden, ever-Shining One.

We Hail!

For Further Reading:

- Bradley, Richard. Midsummer and Midwinter in the Rock Carvings of South Scandinavia .

- Gubanov, I.B (June 2012). “Grave Circle B at Mycenae in the Context of Links Between the Eastern Mediterranean and Scandinavia in the Bronze Age”. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia. 40 (2). Elsevier B.V.: 99–103.

- Kaul, Flemming. The Sun, the Ship and the Horse in Nordic Bronze Age Iconography in Petroglyphs and on Bronze Objects.

- Kaul, Flemming, 1987, Sandagergård. A late Bronze Age Cultic Building with Rock Engravings and Menhirs from Northern Zealand, Denmark. Acta Archaeologica vol. 56, 1985, pp. 31-54, Copenhagen.

- Kaul, Flemming, 1998, Ships on bronzes: a study in Bronze Age religion and iconography. Text. National Museum of Denmark. Copenhagen.

- Kaul, Flemming, 2004, Bronzealderens religion. Studier af den nordiske bronzealders ikonografi. Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab. Copenhagen.

- Kaul, Flemming, 2005, Bronze Age tripartite cosmologies. Praehistorische Zeitschrift 80(2), 135–48.

- Kaul, Flemming, 2006, Kulthuset ved Sandagergård og andre kulthuse – betydning og tolkning. In: Kulthus & dödshus – det ritualiserede rummets teori og praktik, edited by M. Anglert, M. Artursson and F. Svanberg, pp. 99-111, Stockholm.

- Kaul, Flemming, 2010, Hjulkorset – et enkelt, men mangetydigt symbol. Fund & Fortid 2010, nr. 2, pp. 34-39.

- Kaul, Flemming, 2020, The Possibilities for an Afterlife. Souls and Cosmology in the Nordic Bronze Age. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 118, pp. 185-202. Berlin/Boston.

- Kristiansen, Kristian; Suchowska-Ducke, Paulina (December 2015). “Connected Histories: the Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500–1100 bc”. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 81. Cambridge University Press: 361–392.

- Kristiansen, Kristian; Larsson, Thomas B. (2005). The Rise of Bronze Age Society. Cambridge University Press.

- Kristiansen, K., 2010. Rock art and religion, in Representations and Communications: Creating an archaeological matrix of late prehistoric rock art, eds. Fredell, Å., Kristiansen, K. & Criado Boado, F.. Oxford: Oxbow, 92–115.Google Scholar.

- Lind, B.G. and Mörner, N.-A. (2010) Mykenska och Feniciska spår på Österlen. Stjärnljusets Förlag, Malmö.

- Lind, B.G. and Mörner, N.-A. Astronomy and Sun Cult in the Swedish Bronze Age.

- Ma, Yani. Multiple Expressions of the Wheel Cross Motif in South Scandinavian Rock Carvings.

- Mörner, N.-A. and Lind, B.G. (2015) Long-Distance Travel and Trading in the Bronze Age: The East Mediterranean-Scandinavian Case. Archaeological Discovery, 3, 129-139.

- Ranta, Michael; Skoglund, Peter; Rédei, Anna Cabak; & Perrson, Tomas. Levels of Narrativity in Scandinavian Bronze Age Petroglyphs.

- Vandkilde, Helle (April 2014). “Breakthrough of the Nordic Bronze Age: Transcultural Warriorhood and a Carpathian Crossroad in the Sixteenth Century BC”. European Journal of Archaeology. 17 (4): 602–633.

Pingback: Venerating Sunna in Pre-Christian times – a very good article | Gangleri's Grove